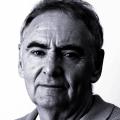

John Byrne may have been born in the year when Churchill became wartime Prime Minister but in almost every aspect of his personality he screamed out to younger generations a personal mantra: ‘Be yourself. Be different.’

The iconoclast, who preached and practised unrestrained possibility and was born into a tenement building in a less-than-salubrious corner of Paisley, was always his own man. Always defiant.

From his schoolyears as a pupil at St Mirin’s Academy, he stood out, the possessor of a defiant, yet comedic voice and a slight eccentric who would write spoof anecdotes of stories in the local papers.

And proved to be quite brilliant with watercolour drawings. This individualistic bent revealed itself through his years at art school and into his working life as a designer at Stoddard’s carpet factory, where Byrne proved to be a character as colourful as the pallets he worked with.

Read more: John Byrne, acclaimed playwright and artist, dies aged 83

What marked John Byrne out was a way of seeing life around him in terms of bright colours and sometimes dark shades. It’s a way of thinking that saw him refuse to attach a label to himself. It appeared in the symbolism of his clothing. He may have grown up in Ferguslie Park, once considered the most depressed housing scheme in Europe, but Byrne was always noticeable.

He determined to raise eyebrows, this tweedy-suited, brogue wearer with the louche silk scarf around his next laughably offered hints of country gent, or eccentric rock star, yet matched his presentation up with the insouciant roll-up that seemed to be surgically grafted to his lips, as a reminder of his working class roots.

Byrne certainly never saw his professional life as being singularly focused. He was always a polymath. His carpet factory experiences gave him the colour with which to write a series of plays, beginning with The Slab Boys. It was a work so powerful it transcended not only its Renfrewshire roots, but Scotland, played out on Broadway by young bucks of the day such as Sean Penn and Kevin Bacon.

John Byrne’s artwork too couldn’t fail to grab the nation’s attention by the throat, evidenced in his album cover work with his old pal from Underwood Lane, Gerry Rafferty. Byrne’s art was deemed to be striking, amusing and populist, and there was little surprise when Billy Connolly asked his friend to design his stage outfits.

Yet, such outrageous talent seldom arrives unaccompanied, and ego – or innate sense of knowing one’s own mind – continually travelled in Byrne’s personal luggage. Actors found his stage plays to be brilliant and clever, but his demands incredibly prescriptive.

The late Freddie Boardley once tried to introduce a bit of acting business to his Slab Boy role – his character entered a church, dipped his comb in the font, and then ran it through his hair – and it was a laughs guarantee. But John Byrne didn’t smile at all.

And Boardley couldn’t for the life of him work out why Byrne was insistent that his character couldn’t, when slapped, say ‘Aya,’ as opposed to ‘Oya.’ Alex Norton, who worked with Byrne back in the Seventies on his 1977 play Writer’s Cramp and found the writer to be ‘a nightmare.’

There’s not arguing however that John Byrne’s fastidiousness, or his passion for his work helped him produce theatre masterpieces such as the bioplay of Scots painters Colquhoun and MacBryde. He would work from early mornings everyday in his garden studio to create his artwork, or batter away at an old typewriter to create his plays.

It was his great insistence on character detail, or the perfect casting, or exactly the right set that would ensure that TV comedy dramas such as Tutti Frutti and You’re Cheatin’ Heart would go on to be adored by the watching public.

Read more: John Byrne: The life and times of the slab boy outsider

John Byrne’s unconventionality, his uncontained imagination was certainly part of his life as a major success story in art, writing and design. It also featured in his personal life, being married to actor Tilda Swinton while accepting an openness of relationship others would have walked away from.

Most people too would most likely have been emotionally destroyed to discover that their father was in fact their grandfather. Not John Byrne. He managed not only to accept the truth but to embrace it, considering that it marked him out to be ‘special’.

There’s little doubt John Byrne was a compelling character. He was an example of what could be possible. He wrote more than 30 plays and screenplays, he illustrated that age need not deny ambition, and last play Underwood Lane ran in Scotland to massive audience appreciation. He said one of the greatest loves of his life was to use language, to play with words and make them sound better.

But there was so much more to the man’s success. He loved to laugh at pretension. He may have looked like a 19th century dandy but that wasn’t about trying to be pseudo aristocratic, that was about laughing at the need to look like everyone else of that moment. And he was bold. To land his first art exhibition in London the young artist sent examples of his work to a gallery, claiming to be his father, Patrick. It worked.

The legacy John Byrne leaves is quite outstanding. And it’s not simply in his body of work. He reminds us of the importance of endeavour, the ritual of commitment that can be so rewarding, and he underlines the belief that there are no limitations to what can be achieved.

Most importantly, while his paintings and writings connected with us, he didn’t simply reflect our world back at us. John Byrne asked us to ask questions. He asked us to think. And we can’t thank him enough for that.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel